Medicaid has historically been an unpopular program with a negative reputation of being welfare for the poor. This is evident in the twelve states that have currently refused to expand Medicaid. This stigma can cause patients to feel shame, inadequacy, and low self-worth when reliant on Medicaid as their sole form of mental healthcare insurance. Patients might feel embarrassed that they can’t afford mental healthcare insurance on their own [2]. Internalized stigma that Medicaid patients may feel is an added stress that hinders access to mental healthcare as it discourages patients from seeking help.

Apart from internalized stigma, Medicaid patients have received suboptimal care. Insurance-based discrimination is when mental healthcare providers unfairly treat patients based on their insurance type, and about 21% of patients with Medicaid reported experiencing insurance-based discrimination, as compared to 3% of patients with private insurance [4].

This difference in how Medicaid patients are treated versus their private insurance counterparts could be partially due to dissatisfactory physician opinions towards Medicaid and its low reimbursement rates. Physicians get paid the highest fees when treating patients with private insurance, but they get paid the smallest fees when treating patients with Medicaid. This is because private health insurance companies offer physicians higher reimbursement rates for the services that patients incur, whereas Medicaid, on the other hand, offers physicians low reimbursement rates. Thus, physicians have financial incentive to prioritize private insurance patients over Medicaid patients. In fact, in 2011 nearly one-third of physicians were unwilling to accept new Medicaid patients [3]. Medicaid beneficiaries are consequently subject to more difficulty when trying to find a provider.

Stigma around Medicaid also has adverse effects on patient mental health. It can manifest into delayed care, unmet needs, and forgone care. One study found that those who reported frequent insurance-based discrimination were also more likely to experience delays in seeking mental healthcare [1]. Because Medicaid patients have a smaller network of providers, the process of finding an adequate provider could delay the necessary care that they would have gotten if they were privately-insured. Additionally, of the Medicaid patients who reported frequent discrimination, 31% also reported receiving no preventative care within the last year [1]. This further illustrates the extent of unmet needs and forgone care. The stigma coupled with a lack of primary care could lead to higher chances of developing health conditions that could be more intensive and expensive to treat down the line.

As of May 2021, the total number of Medicaid enrollees is 75.9 million [5], accounting for approximately 23% of the US population, and this number has been increasing for the past twenty years. Stigma surrounding Medicaid and the effects it has on patient health is even more pronounced considering its large scale. Medicaid patients face unequal barriers to healthcare as seen with insurance-based discrimination and the adverse health outcomes that result from it, which ironically contradicts the ACA’s fundamental goal of improving health quality and access. In order to work towards achieving health equity, healthcare providers and policy makers must understand the negative health effects surrounding the stigma around Medicaid and the added health barriers Medicaid patients face.

The growing mental health crisis places an increasing and disproportionate burden on Medicaid, a new study shows.

An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation notes that 39% of Medicaid enrollees live with a mental health or substance abuse problem. Providing mental health services costs Medicaid more than it does any other payer, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

KFF surveyed Medicaid officials in 44 states to find out how they intend to meet the challenges behavioral health conditions present in 2023 and beyond.

“State strategies to address the behavioral health workforce shortage fall into four key areas: increasing rates, reducing burden, extending workforce, and incentivizing participation,” the KFF analysis said.

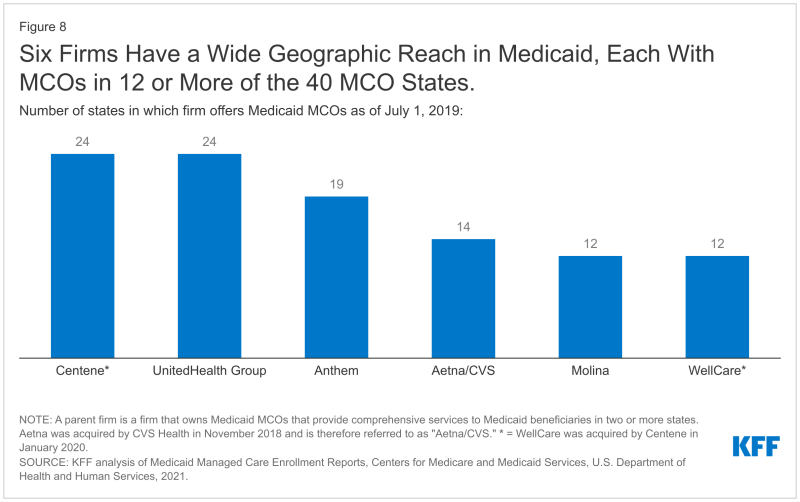

Because most Medicaid enrollees receive coverage through health insurance plans, those companies will be intricately involved in addressing the crisis. Making sure enrollees have access to mental health specialists such as psychiatrists challenges not only Medicaid but the entire healthcare system.

Primary care physicians provide most of the mental health care in the country because there are simply not enough psychiatrists and other specialists in that category available.

However, help may be on the way thanks to the Consolidated Appropriations Act (PDF), passed in December. The act authorizes funding for at least 100 new psychiatric residency programs. In addition, the act allows more providers to subscribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

Psychiatrists are paid about the same as PCPs for delivering the same services, a fact that discourages their taking on Medicaid patients, according to KFF. In Medicaid fee-for-service, states have more leverage to ensure psychiatrists are paid more.

“Managed care plans, which now serve most Medicaid beneficiaries, are responsible under their contracts with states for ensuring adequate provider networks and setting rates to providers, but states have several options to ensure that rate increases are passed to the providers that contract with managed care organizations,” the KFF analysis said.

Most states that contract with MCOs told KFF that they would start requiring that MCOs implement FFS rates for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. “A smaller share of MCO states do not require, but may encourage, MCOs to implement FFS rate increases,” the analysis said.

Some states targeted pay increases for providers that deal with specific problems, such as substance use disorder. Other states made across-the-board moves, such as Oregon, which directed MCOs to increase payments by 30% for providers who get 50% of their revenue from Medicaid.

To extend the workforce, some states will widen their scope of practice, allowing more providers to care for mental health patients. Some providers, such as social workers in New Jersey, will now be able to bill Medicaid directly for serving mental health patients.

“Most states with MCOs reported that requirements in FFS were also required for MCOs,” the KFF analysis said. “Adding peer or family specialists as providers was the most commonly reported strategy for expanding the workforce.”

Interprofessional consultation will be given more leeway. For instance, PCPs in rural areas would be reimbursed for consulting with psychiatrists to discuss medication management. CMS recently ruled (PDF) that such consultations can be billed as a distinct service. “While access to specialty care has been a challenge across a range of specialties, access to specialty care for mental health and substance use disorders has been a particular challenge,” CMS states.

CMS pointed out that Medicaid enrollees have higher rates of chronic diseases in general, conditions that behavioral health problems exacerbate. “While interprofessional consultation is key to expanding access to behavioral health services, it can also be an effective component of expanding access to specialty care for physical health conditions, particularly in rural and remote areas that may be lacking specialists,” CMS said.

CMS also encourages the use of telehealth for mental health services for increasing “retention in substance use disorder treatment, including medication-assisted treatment, especially when treatment is not otherwise available or requires lengthy travel,” CMS stated.

The “hassle factor” vexed physicians, since managed care via health plans first rose to prominence in the early 1990s. It covers many plan-mandated requirements that doctors didn’t face before and don’t appreciate now, such as needing to get prior authorization to do certain procedures, the implementation of capitation—which detractors complain pays doctors based on the volume of patients treated rather than quality—and having to maneuver through a bureaucratic minefield if they accept patients from different health insurance plans, which most doctors do.

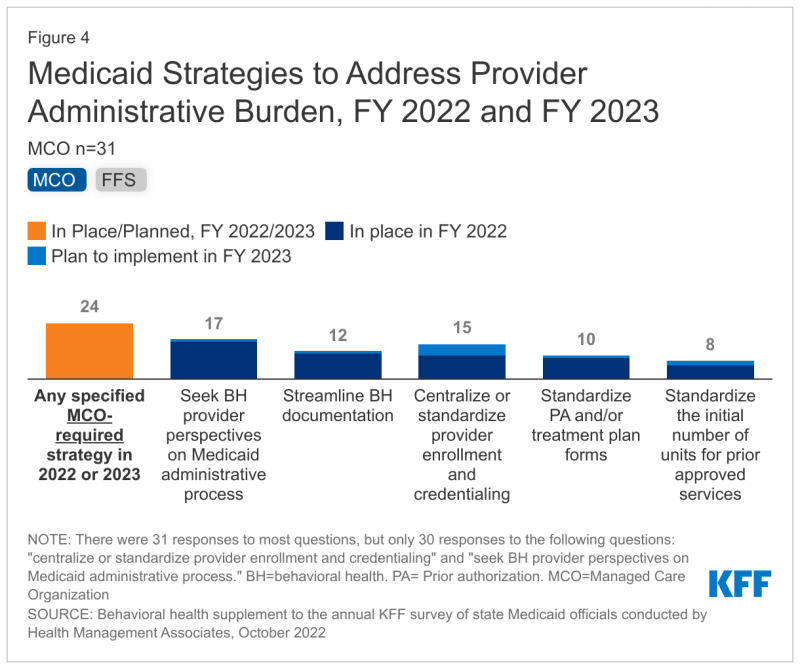

In dealing with mental health in 2023, states encourage managed Medicaid to reduce the administrative burden responsible for that paperwork.

“Providers contracting with multiple MCOs may notice that administrative requirements and processes vary between MCOs due to the lack of standardization at the state level,” the KFF analysis said. “Varying administrative burdens may be particularly challenging for smaller behavioral health providers/organizations. Thus, addressing administrative burdens could reduce time associated with unbillable provider time and resources and result in higher rates of Medicaid acceptance.”

About three-quarters of states tell KFF that they want to decrease administrative burden in both FFS and managed Medicaid. Some want providers to tell them how best to do that. “Somewhat fewer states reported standardized prior authorization, treatment plan forms, or initial number of units or days for prior approved services,” the KFF analysis said.

Still, reducing the hassle factor when it comes to serving Medicaid enrollees with behavioral health issues will require a changed approach, and it certainly won’t be easy. “As an example,” the KFF analysis said, “one state noted that their state’s behavioral health authority also regulates documentation, so efforts to streamline documentation require collaboration between the two agencies.”

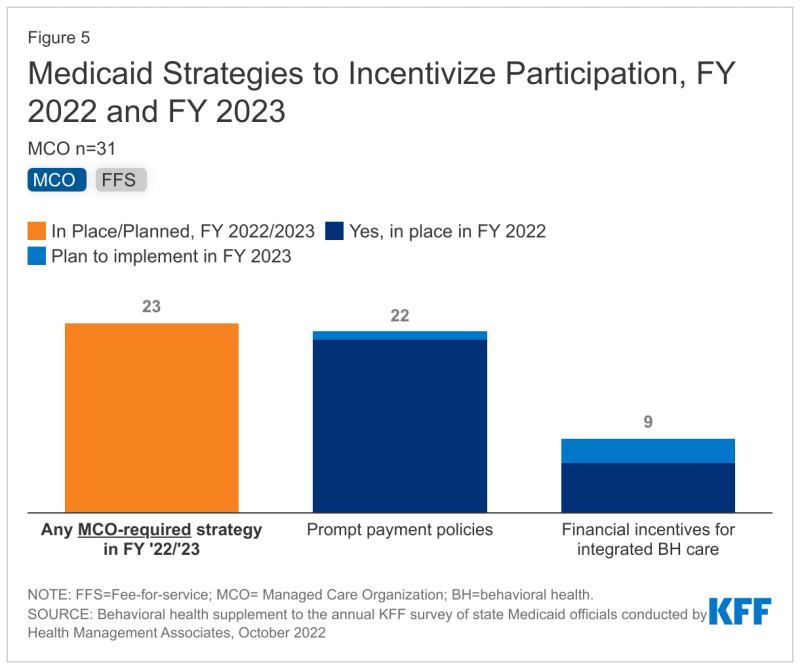

State Medicaid officials told KFF that to effectively care for individuals with behavioral health problems, providers need to be paid fairly and in a timely manner in both FFS and managed Medicaid.

“In North Carolina, for instance, health plans must notify providers within 18 calendar days of any additional information needed to process a claim and they must pay for approved clean claims within 30 calendar days,” the KFF analysis said. “Some states may choose to use financial incentives to encourage providers to participate in integrated physical and behavioral health systems, with some incentives aimed at increasing behavioral health screenings or developing the workforce.”

Of course, Medicaid is a joint state and federal program, and KFF researchers argue that the Consolidated Appropriations Act ensures that the federal arm will do its share in fostering improvements in mental healthcare for managed Medicaid. The act requires “additional training on treating and managing patients with OUD or SUD for all prescribers of controlled substances. Other relevant provisions include grants for mental health peer support providers and requirements to improve the accuracy and usability of Medicaid provider directories, which have been shown to be particularly inaccurate for mental health.”

References:

-

Allen, E. M., Call, K. T., Beebe, T. J., McAlpine, D. D., & Johnson, P. J. (2017). Barriers to Care and Health Care Utilization Among the Publicly Insured. Medical care, 55(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000644

-

Allen, H., Wright, B. J., Harding, K., & Broffman, L. (2014). The role of stigma in access to health care for the poor. The Milbank quarterly, 92(2), 289–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12059

-

Decker S. L. (2012). In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health affairs (Project Hope), 31(8), 1673–1679. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294

-

Han, X., Call, K. T., Pintor, J. K., Alarcon-Espinoza, G., & Simon, A. B. (2015). Reports of insurance-based discrimination in health care and its association with access to care. American journal of public health, 105 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), S517–S525. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302668

-

Medicaid.gov. May 2021 Medicaid & Chip Enrollment Data Highlights. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.