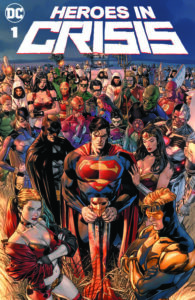

DC Comics’ ‘Heroes in Crisis’ Examines the Psychological Turmoil Beneath the Costume, from PTSD to Addiction

Comic book fans would admit that their favored genre is filled with wacked-out dude-bros chosen at random to possess powers the rest of us could only dream of. In fact, comics are actually a lot like the real world: Their heroes suffer a physical and psychic toll as a result of cyclical violence. The best comic book writers and artists unravel the turmoil that follows those responsible for holding up an entire galaxy with deft, style, and consideration. That friction is the main theme of DC Comics’ Heroes in Crisis, the latest endeavor from writer Tom King and artist Clay Mann. An early example of this friction appears in the premiere issue, in which King cleverly turns the struggle of Blue Jay—a Justice League rotational player beginning to lose grasp on his shrinking power—into a genuine testimony on the ways depression breeds stasis: “I go to sleep,” said the hero. “And wake up small … I’ll be drowning in my own bed.”

Heroes in Crisis is set at the Sanctuary, a futuristic, super-secret psychiatric hospital in the desert. Its powerful patients are reeling after a mass murder of heroes at the facility including B-listers like Hot Spot and major players like Wally West, a.k.a. the Flash. Despite the comic’s somewhat ham-fisted promotion as being “ripped from real-world headlines,” Heroes in Crisis writer King understands acts of violence and the scars they leave on costumed heroes better than most. He interned at both Marvel and DC before becoming a CIA officer for seven years. His inspiration for Heroes in Crisis stems from his own war experience: “We have this generation, my generation, cycle through the Middle East and back and I think that experience is driving us a little crazy and I think we need to talk about that—talk about the honor of that service and how the honor of serving is incurring a little damage along the way.”

As one could imagine, this kind of endeavor—elucidating the mental health struggles of superheroes while also alluding to the reality of perpetual war—is a political minefield. The widely discussed comic has become the topic of thoughtful ruminations on the psyche of veterans and other trauma survivors, but has also drawn controversy due to its subject matter and the ways that the writer-artist team has executed the themes of interpersonal isolation, repression, and addiction.

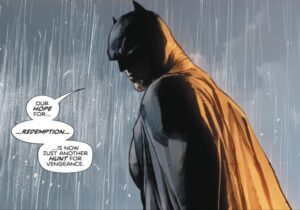

Heroes in Crisis is now on the shortlist of modern comic arcs that perform psychological jiujitsu on fans by arm-dragging DC figures—both influential and seemingly inconsequential—to eye level. Consider it Dr. Melfi for those who don spandex, a reminder that nuclearly powerful, ego-boosted heroes are subject to the same anxious, depressive cycles plaguing the lot of us. We already know that superhero origin stories routinely cover such horrors as murders in dark alleys, abandonment, and crass government experimentation—backstory elements that are often used to add gravitas to a vigilante’s resolve to stop crime and evildoers. But while the tragic narrative beats of DC’s Trinity—Superman’s struggle between two identities, Batman’s trail of dead sidekicks, and Wonder Woman’s fight against her own nature—are well-known, the problems befalling the imprint’s second string characters are more obscure. The inclusion of characters like Commander Steel, Solstice, and Booster Gold in Heroes in Crisis makes the series feel more reachable and a bit more human.

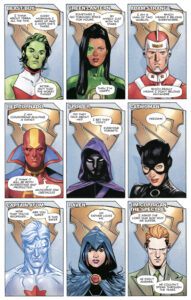

Heroes in Crisis is particularly harrowing in the ways it “adjusts the camera,” in King’s words. It casts readers as sounding boards for costumed icons to come clean about their anguish—an anguish that doesn’t fall back on origin stories, but instead draws on the violence of the present world. Over the course of each story, heroes speak directly to readers and, in confidence, reveal the psychological struggles that are hidden beneath the costume. Some are more game than others—Black Canary, for instance, says “fuck it” and walks out of the confessional almost immediately. But on the whole, these sessions are heart-rending micro-stories that touch on the feelings heroes subdue in order to keep doing their jobs effectively.

Within the story, DC’s aforementioned Trinity established the Sanctuary as way to serve the therapeutic healing that some heroes need when their other fixes don’t hit. The audience is positioned as a camera (which, in the world of the comic, is a 24th-century computer that keeps their confessionals secret). In the first issue of Heroes in Crisis, former Green Arrow sidekick Roy Harper (a.k.a. Arsenal) identifies as both hero and addict and has a personal tale entwining the decades-long opioid crisis, superhero idealism, and the pharmaceutical industry. He fidgets in his chair while recounting to us how he got here: “You get six doctors, 14 pharmacies, plus a guy who’s not really a doctor. Another guy who’s only kind of a pharmacist. And one day you read somewhere that you’re killing your kidneys … so you go to a needle. To save your kidneys … But really, isn’t that what superheroes do? Save things?” When humans project righteousness onto singular figures whose trade is violence, the pedestal can warp reality and rip them to shreds. King compares the mental acrobatics required of superheroes to the “attitude of football players not talking about concussions. You know in the back of your head it’s not good for you, but you don’t wanna be that guy.”

When King was asked about the model for Sanctuary, he remembers a mid-desert oasis full of young people needing a cooldown in the heat of war. During his time in Iraq, King recalls being sent to this facility “for folks who had seen too much but weren’t ready to go home.” At the time, it was full of young men—King then being only 23—and the curiousness of that scene eventually sparked the idea that became Heroes in Crisis: “That’s where it started: like what an odd place in this middle of this desert in the middle of this war and there are kids playing in a pool because they couldn’t face another day with a gun,” he said. “But they still had to go back.”

At times, the characters seem mishandled. The trauma depicted within the pages of Heroes in Crisis might seem like it’s being trivialized for any reader feeling the agony of depression, addiction, or a surplus of anxiety. On the whole, the comic book industry still has room to grow when it comes to addressing real-life social problems without exploiting mental health struggles and marginalized populations.